One day, I was cutting the grass and pondering the nature of the universe.

I watched the grass clippings as they were ejected from the mower, each falling perfectly to the earth.

I wondered how gravity was accomplishing its job on the clippings. By what mechanism was each pull accomplished so precisely?

I thought of all the ways in nature that I could think of in which things are pulled. To pull, something must be latched onto or captured by something. In all those natural cases, an arm, a hand, a rope, a string, a cable, a net, a hook, or something—anything is connected to an anchor point, latches on, and pulls.

That's when I wondered ...

How is it that something is always latching on, hooking up, and towing each and every one of these grass clippings towards the center of the earth? And, if so, what is used to latch on? Where's the anchor point? What cables are being used? How is each and every one always connected? Why do none ever escape? Where are these pulling devices hidden when they aren't pulling?

Thinking about it this way, the concept of gravity pulling in nature doesn't work. In fact, it's absurd.

This realization led me to look at things from the entirely opposite direction—truly 180 degrees.

I thought, if these clippings aren't being pulled, then what's happening to them?

What if they are being pushed?

That's when I realized that nature pushes things into place—almost everywhere you look.

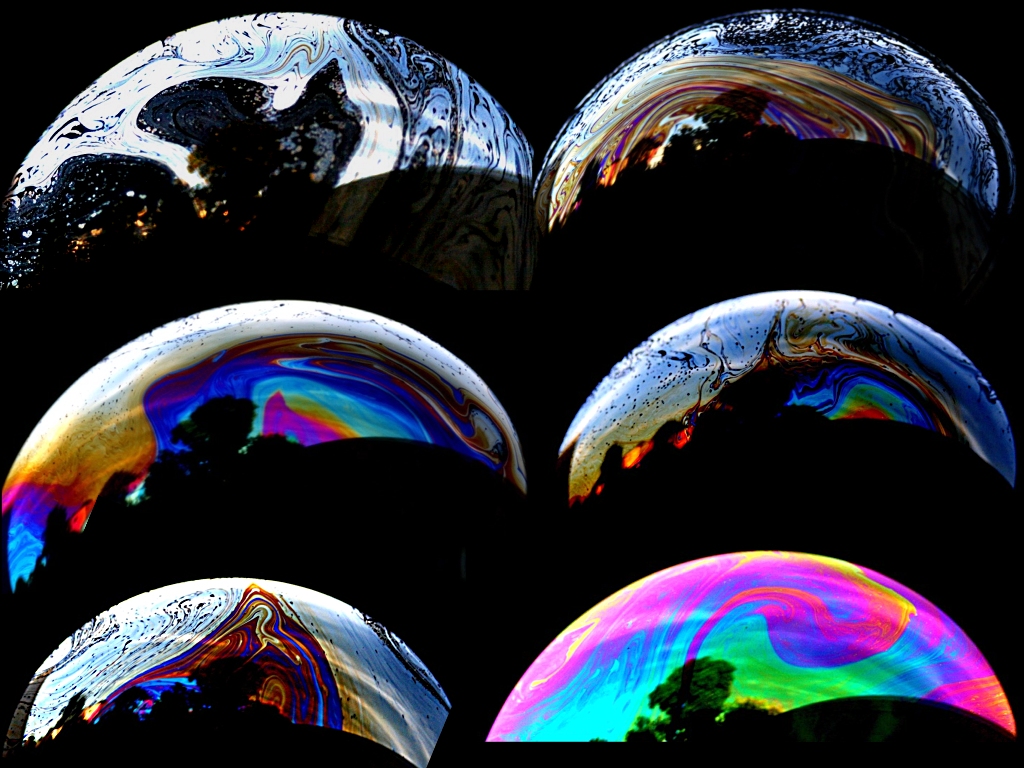

Examples: Air pressure forms bubbles, pushing everything to the center of a sphere. Water pressure forms bubbles, pushing everything to the center of a sphere.

Therefore, why isn't gravity the same? Why, like in air and water, aren't these grass clippings being pushed by outward pressure towards the center of the sphere of the Earth?

This is the line of thinking that began the journey for me.

And was thrilled to find that others have travelled this path ...

Upon research into push gravity, the first I found was Walter Wright, author of the 1979 book Gravity Is a Push, where he proposed gravity as a pushing force based on years of research.

Later, I found that Einstein had considered mechanical explanations for gravity, though his theory of general relativity ultimately described it as the curvature of spacetime.

And most recently, I've learned of Le Sage, whose 18th-century theory explained gravity through streams of tiny particles pushing matter together.

These concepts are not new, but their application to unification may be or apparently is.

I'm grateful to join these others and more on this wonderful journey.

References

- Wright, Walter C. (1979). Gravity Is a Push. Carlton Press, New York. 176 pages. This book presents an alternative theory where gravity is explained as a pushing force rather than a pull, drawing from the author's decade-long research and experiments. Available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/GravityIsAPushbyWalterCWright.

- Einstein, Albert. (1915). General Theory of Relativity. Einstein's groundbreaking work revolutionized our understanding of gravity, describing it not as a mechanical force but as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. While he explored mechanical explanations earlier in his career, his final theory emphasized geometric properties over traditional attraction. For more details, see: Wikipedia - General Relativity.

- Le Sage, Georges-Louis. (1748). Le Sage's Theory of Gravitation. This 18th-century mechanical theory posits that gravity results from streams of tiny, unseen particles (ultra-mundane corpuscles) bombarding matter from all directions, with bodies creating "shadows" that produce a net pushing force toward each other. It was one of the most developed push-gravity models of its time. Further information available at: Wikipedia - Le Sage's Theory of Gravitation.

Credits

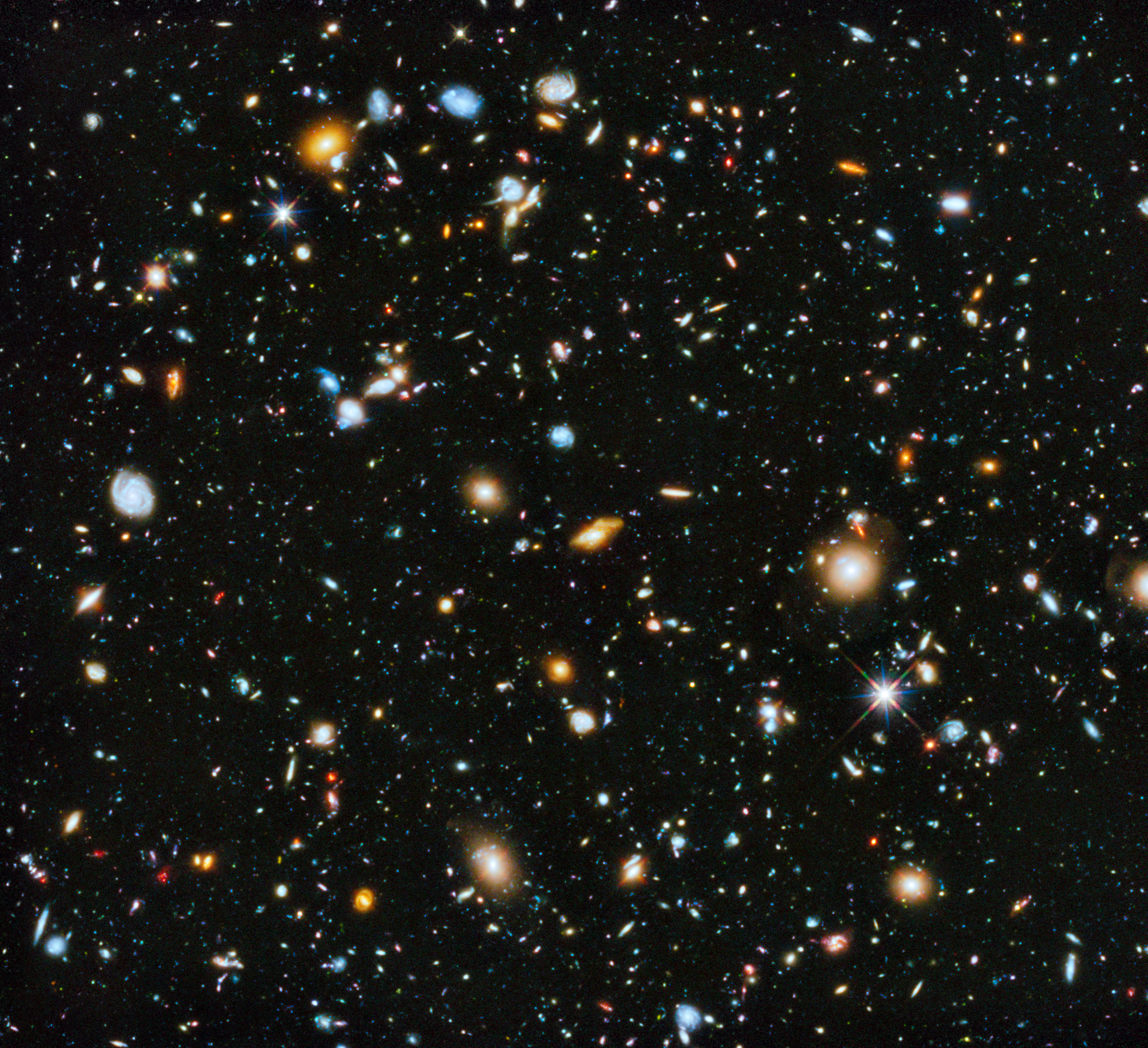

This article was edited with assistance from Grok, an AI built by xAI, to refine structure, clarity, and flow while preserving the original voice and ideas. Images created with Google AI.